battle-scarred Afghanistan, following the fall of Kabul, with an indiscreet and cumbersome cherrywood plate camera. These remarkable images, as Jason Burke commented in The Observer Magazine, " …reveal a post-apocalyptic landscape devoid of people, but shot through with a surreal and barren beauty."

European art has long had a fondness for ruin and desolation that has no parallel in other cultures. Since the Renaissance, artists such as Claude Lorraine and Caspar David Friedrich have painted destroyed classical palaces and gothic churches, bathed in a fading golden twilight. These motifs symbolised that the greatest creations of civilisation – the Empires of Rome and Greece or the Catholic Church - even these have no permanence. Eventually, they too would crumble; vanquished by savages and vanishing

into the undergrowth.

Afghanistan is unique, utterly unlike any other war-ravaged landscape.

In places destroyed in the recent US and British aerial bombardment,

the buildings are twisted metal and charred roof timbers (the presence

of unexploded bombs deters all but the most destitute scavengers) giving

the place a raw, chewed-up appearance.

Norfolk writes-

Afghanistan is unlike Sarajevo or Kigali or any other war-ravaged landscape I have ever photographed. In Kabul, in particular, the devastation has a bizarre layering …I was reminded of the story of Schliemann 's discovery of the remains of the classical city of Troy in the 1870s: digging down, he found nine cities layered upon each other, each one in its turn rebuilt and destroyed. Walking a Kabul street can be like walking through a Museum of the Archaeology of War -different moments of destruction lie like sediment on top of each other. There are places near Bagram Air Base or on the Shomali Plain, where the front line has passed back and forth eight or nine times -each leaving a deadly flotsam of destroyed homes and fields seeded with landmines.

The landscapes of Afghanistan are the scenes that I knew first from the 'Illustrated Children's Bible' given to me by my parents when I was a child. When David battled Goliath,these mountains and deserts were behind them …More accurately, these landscapes are how my childish imagination pictured the Apocalypse: utter destruction on a massive, Babylonian scale, bathed in the crystal light of a desert sunrise.

Questions:

- Norfolk photographs with a large, cumbersome, wooden camera that is very different than the small SLR-type cameras most photojournalists use. How does this make his images different from a typical journalistic image you would see in a newspaper?

- How do you think Norfolk's images reflect the sense of "walking through a Museum of the Archaeology of War?"

- How would you compare Norfolk's work to that of Edward Burtynsky, in Ch. 3?

6 comments:

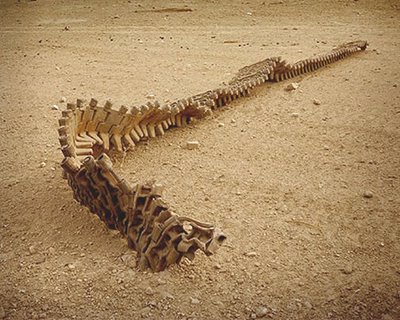

With a camera that Norfolk uses I think it takes a lot more time and consideration to compose a photograph. You can’t just snap a photo, with this one it takes time to set the camera up, focus, and make the composition. Burtynsky and Norfolk have very similar styles. I think in both of their works the photographs that are void of people are the most intriguing. It seems that Burtynsky is more detached form his subjects than Norfolk. Norfolk has a relationship with what he is shooting, they comes across as very personal. I really like the photograph of the tank tread. It looks like the spine of a great beast left to be bleached out by the sun.

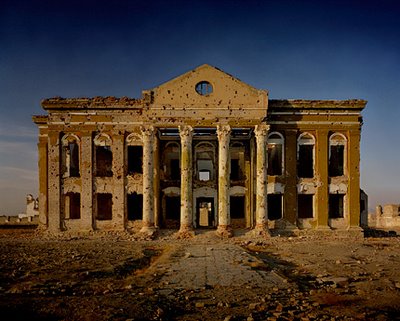

I think these are pictures are much, much different than anything one might find in a newspaper. I think they are so much more beautifully composed, the colors are awesome in so many of them. It seems as though they took much thought and time in composing. I wonder if that picture of the stage thing used to be a movie theater or a theater theater. I love the photograph of the two parts of the plane with the palm branches framing the picture. There's some sign in the middle of the two parts; I really wonder what it says, like if it's some kind of memorial or something that was already there. There've been a few different photographers whose photos don't have titles. It really gives it more meaning when they do. It also helps me to interpret them, or at least know what the photographer wanted to say about it. I alos really like the print of the building that looks like a cross between the Parthenon and the Alamo. I like how the color of the ground runs/flows into the color of the building, it makes the color of the sky pop that much more. I also really like the thousands of bullets picture. So much detail; it took me a sec to figure out what they were but that makes me like it all the more. If I were seeing it in person instead of on a computer, I probably would've known. I actually like all the ones that are outdoors better than the ones inside; contrasting the beauty of the sky against the ugliness of a "war-ravaged landscape".

These destroyed places have yet to be rebuilt, or even cleaned up, and it seems they may never be. So to me, they stand as exhibits of destruction. It reminds me of when you go to a museum that is having an exhibit of an ancient culture and they recreate a little part of the architecture. Except this is no recreation, of course.

The places that Norfolk has photographed are easily related to: a movie theatre, a home, a building that looks like it could have been a library or court of some kind. I think that adds a great deal to the museum quality of it.

The quality of the image through such a large format camera is clearly better and there are traces of vinetting. the shots of common places like the thearter in ruins shows up like a archelogical dig of a post apocolyptic society.

His images are clearer and more carefully composed than that of a newspaper image. This makes them special to the viewer, instead of just photos of devistation. My favorite is the one of the man standing with the caged bird in front of the large bird that is in such bad shape it too is trapped near the ground.

Post a Comment